Regulated carbon markets and the evolution of the Voluntary Carbon Market (VCM)

This is a long form primary research on the regulated and voluntary carbon market (VCM) and its likely evolution. I will post separate blogs breaking this out, but I’ve had a number of clients (including investors who are looking at investing in nature based solution projects) ask for this primary research.

All links to this content are provided at the bottom of this document.

Also note that the market has evolved considerably from June 2023 (when this research was done) with new guidance for projects and project developers. I will write separate blogs around these.

Exec summary

Differences between carbon credits (compliance-based market) and the VCM (Voluntary Carbon Market)

VCM: Societe Generale explanation:

2. What are the key challenges facing the development of this market and how would you address them?

Legacy vs evolving Voluntary Carbon Market

The legacy Voluntary Carbon Market

The underappreciated role of carbon insets in decarbonizing Scope 3 supply chains

(1) Carbon emissions tracking - who owns the emission reduction?

(2) Standards setting - who makes the methodology and standard?

Inset Adoption is ripe in Food & Ag

Carbon Insets in the real world

Summary

Exec summary

There are 2 carbon markets; a government/body ‘cap n trade’ market such as the EU’s ETS (Emissions Trading Scheme) which deals in carbon credits, and the Voluntary Carbon Market (VCM) which deals in offsets.

The EU ETS was founded in 2005 and has traded in permits ever since, whereas the VCM has grown very quickly over the past 2-3 years, driven by companies’ commitment to (voluntary) Net Zero targets.

ETS permits are often called carbon credits, whereas the VCM market deals in offsets. Sometimes those terms are used interchangeably in the press, which has caused a lot of confusion.

Our focus in this blog is to explore the evolving nature of the VCM - although we do touch on the ETS/Carbon credits system.

The VCM market is quickly evolving, with a lot of new market entrants

What is clear in the VCM is that the market is quickly evolving, and market actors such as Verra, Gold Standard etc will evolve to regain market confidence. We will see a raft of new market entrants across the ecosystem, which we will touch on in this blog.

We are also likely to see a lot of market consolidation, and offset buyers (both corporate and investor) are likely to use software marketplace platforms to buy/sell offsets, perhaps in addition to the current use of brokers.

This new landscape will evolve over the next few years - the new tech-enabled market entrants will need time to develop their customer base and integrate with each other. Also, given current market conditions, it will be hard to raise a Series B or C at terms which are advantageous to the tech scale-ups until probably mid-late 2024.

However, it seems clear that technology will solve some of the current challenges around transparency and quality. It may also make it easier to raise capital to develop projects and increase liquidity in the VCM.

VCM Market drivers

From 2023 regulations (such as the EU CSRD and others) will force ever more companies to disclose their carbon emissions, and companies that have publicly committed to NetZero targets may start to see real pressure to decarbonise. 2025 could be a crux year for companies, with pressure ratcheting up both from regulation and from investors (not to mention their customers & other stakeholders).

Note: We discuss Net Zero and Scope 3 (supply chain carbon emissions) in this deck, click through to these links for a quick brief on Net Zero, and what Scope 1, 2 & 3 actually mean.

Differences between carbon credits (compliance-based market) and the VCM (Voluntary Carbon Market)

Societe Generale have provided a useful explanation, which is copied below

1. What are voluntary carbon markets and how do they differ from carbon taxes or other regulatory schemes?

Carbon markets refer to trading schemes in which carbon credits are sold and bought, similarly to other forms of financial instrument trading. And here, the traded underlyings are carbon credits, where each credit represents one metric tonne of carbon dioxide equivalent.

There are two main types of carbon markets: compliance and voluntary.

Compliance carbon markets, also called Emissions Trading Systems (ETS), are created as a result of national, regional or international policy or regulatory requirements.

They are essentially marketplaces through which a certain number of carbon credits are assigned per company and per year, allowing them to emit the equivalent amount of carbon or to sell their credits if they emit less than their quota.

Market participants – often including both emitters and financial intermediaries – can trade allowances to make a profit from unused credits or to meet regulatory requirements. There are approximately 30 ETS implemented globally, covering 38 national jurisdictions with many more countries and states considering implementation.

2. Voluntary carbon markets refer to the issuance, buying and selling of carbon credits on a voluntary basis.

Here, voluntary carbon credits are issued in respect of nature or technology-based projects aiming at reducing or removing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, once these projects’ benefits have already occurred. For instance, carbon capture is a removal project type and may be achieved through natural (e.g. reforestation) or technological (e.g. direct air capture) strategies.

These credits can then be sold to corporates, financial institutions, or individuals to support emissions reduction commitments by retiring voluntary carbon credits. This market is neither legally mandated nor enforced but self-governed.

In 2021, COP26’s wakeup call with regards to meeting the Paris Agreement targets by 2050 created a strong momentum for carbon finance and significantly boosted the profile of the voluntary carbon market.

That year, market transactions in voluntary carbon markets nearly quadrupled the previous year value towards USD 2 billion. While this is still far smaller than the current global compliance market value of USD 850 billion in 2021, our view is that there will be an increasing number of companies working to meet their decarbonisation commitments, thus contributing to the development of the voluntary carbon market.

As such, the overall price of voluntary credits is expected to rise, and a more active secondary market is anticipated.

Societe Generale: We estimate that the voluntary carbon market size will reach approximately 2.5 billion tonnes in 2030 for a corresponding market size of about USD 100 billion.

(Source: Taskforce on scaling voluntary carbon markets and Trove Research)

2. What are the key challenges facing the development of this market and how would you address them?

Voluntary Carbon Markets (VCMs) are relatively new and face several challenges. For one, they lack adequate liquidity, notably due to carbon credits being heterogeneous in terms of quality, price transparency, and certification methodologies. This in turn leads to pricing issues as the lack of transparency makes it difficult to set a market price as the true value of the credits. Project developers also lack access to finance because of market opacity and a low investor risk appetite. Additionally, they lack the capacity to efficiently market their credits to multiple buyers.

These challenges call into question the framing of this market, and the lack of standardisation within. While some may see daunting issues, others see teething problems that can be fixed.

While not exhaustive, and at this stage purely prescriptive based on our own views, some useful steps to scale-up this market into a reliable and a safe ecosystem include:

• Definition of common features for carbon credits: buyers and suppliers would interact more efficiently if all credits had common features including quality criteria and attributes standardised in a common taxonomy.

• Uniformity of contracts with standardised terms: making carbon credits tradeable with standard attributes and size would consolidate trading activity and promote liquidity on exchanges. Reference contracts tend to make it easier for companies to purchase large quantities of carbon credits.

• Enhancing trading and post-trade infrastructure – including Clearing Houses.

• Implementing mechanisms to safeguard the market’s integrity: establishing a digital process, through Blockchain for example, by which projects are registered and credits are verified and issued, resolving the double counting issue which is important to legitimise the market.

• Attracting institutional investors: as of today, institutional investors are not very present in the VCM due to the limited liquidity and price transparency.

And of course, recognising the importance of the VCM in the net zero transition, as the required last step to offset non-abatable emissions, the wider industry is working together on these governance and market scaling initiatives.

As alluded to above, standardisation is key and that is exactly what the Integrity Council’s Expert Panel, made up of twelve leading carbon market experts, is working on via its Core Carbon Principles.

The objective is to set new threshold standards for high-quality carbon credits that will support the increased financing requirements and the price discovery. Societe Generale recently formalised their participation to this initiative which is supported by 250+ member institutions from all horizons including a large part of our peers.

And as an added bonus, the above-mentioned steps and initiatives would also help reduce the greenwashing risk thanks to the definition of a common set of quality standards.

The carbon credits market (compliance-based)

CCMs are also referred to as emissions-trading systems (ETS) or cap-and-trade programs. They are marketplace mechanisms where regulators auction off, or distribute for free, a limited number of carbon allowances to various regulated companies

Source: https://www.msci.com/www/blog-posts/introducing-the-carbon-market/03227158119

Carbon allowances traded in primary and secondary markets

Carbon allowances are traded in both primary and secondary markets. Regulators typically auction, or distribute for no cost, allowances to regulated entities through primary markets to comply with their emission limits. Once regulated companies are allotted an allowance, they can trade it in secondary markets (in line with their emission requirements) using both spot or derivatives contracts such as futures, options and swaps. A view of the various stakeholders involved in compliance carbon markets is shown below.

Source: https://www.msci.com/www/blog-posts/introducing-the-carbon-market/03227158119

Carbon trading

Carbon credits (as opposed to offsets) are allowances from government entities that can be purchased from companies that went over and above in their emission reduction. Because one company reduced more than necessary—another company can purchase the “difference” to cover their inability to meet the current standard.

Futures contracts are created with these allowances—or credits—as well. Companies can enter into a contract with each other to sell and buy carbon credits at a later date.

The supply of these allowances in the EU (by far the largest ETS market) is controlled by the EU ETS marketplace, which means the price is directly influenced by it. Price too low? The marketplace simply reduces the number of given credits. Problem solved.

The interesting part is that anyone—individuals, investors, companies, hedge funds—can invest in this carbon futures market by investing in ETFs that purchase the futures contracts. The futures contract for EU ETS is known as the European Union Allowances or EUA. The existence of the EUA futures market has led to some controversy.

Speculation by outside investors could negatively affect the original goal of the ETS—to reduce pollution—by influencing the futures’ price to reflect speculative decisions instead of marketplace decisions.

Conversely, outside investors create liquidity in the market, potentially making the price more accurate—instead of allowing only the EU to influence the price through its supply.

It’s unclear whether investing in mandatory reduction-driven ETFs is a good investment. Futures contracts only produce a profit if the price at the time the futures contract matures is greater than the futures price when the contract was entered into.

In 2021, the price of the European Union Allowances future contract nearly doubled in response to an announcement by the European Union that it wanted to expand emissions caps to additional industries.

With the EUA priced at around 84 Euros (As of end April 23), speculators in these futures will need to see a EUA price higher than that in order to earn a profit.

Carbon market trading platforms

There are a number of platforms where you can hedge & trade carbon credit futures and trade on spot exchanges:

Example of hedging options:

The KraneShares Global Carbon Strategy ETF (KRBN) is benchmarked to IHS Markit’s Global Carbon Index, which offers broad coverage of cap-and-trade carbon allowances by tracking the most traded carbon credit futures contracts. The index introduces a new measure for hedging risk and going long the price of carbon while supporting responsible investing.

Some example trading exchanges (including spot):

CTX

Xpansiv

ICE: ICE has launched 10 carbon credit futures.

LSE proposed VCM (as of November 2022) but as of today not yet operational.

Source: https://www.londonstockexchange.com/raise-finance/equity/voluntary-carbon-market

Regulation for Carbon Credits Markets & VCM

IOSCO (International Organisation for Securities Commissions, they are the International forum for national securities & futures regulators) published 2 papers in Nov 2022 that propose regulatory changes in the carbon credits market (Compliance-based) and a discussion paper on the VCM.

Regulation in the Carbon Credits Market (Compliance)

Key Issues: At a high level, the issues are rooted in the following:

Conduct - including conflicts of interest between market participants.

Lack of transparency, oversight and monitoring of trades.

Fraud, insider trading and price manipulation.

IOSCO’s 12 recommendations deal with the primary market, market integrity, and market transparency and structure.

Regulation in the Voluntary Carbon Market

IOSCO has proposed to work closely with the Integrity Council for the Voluntary Carbon Market (ICVCM), an organisation which has proposed a core set of principles (Core Carbon Principles - see below visual).

However, doubt has been cast over their principles, which included re-certifying all existing carbon credits, an “impossible” policy according to Verra.

With new entrants into the market that can provide transparency and data to market participants (see content below on emerging tech-enabled MRV providers), IOSCO may leave the VCM to evolve and step in only if necessary.

There don’t appear to be any regulatory changes expected in the short-medium term in the VCM, partly because it’s not governments that are mandating the use of a VCM market. As noted throughout this blog, it’s really the corporates’ Net Zero commitments that are driving the demand for offsets.

The relationship between Net Zero commitments and Offsets

Some context: Around 20 years ago, companies began voluntarily submitting their carbon emissions data to the Carbon Disclosure Project (CDP). Now 20,000+ organisations are voluntarily submitting their carbon emissions to CDP - which they use to signal their environmental achievements & goals to stakeholders and investors (The E in ESG).

However, now regulatory disclosure is coming (CSRD in the EU, SECR in the UK, the SEC is working on its equivalent). The CSRD is going to effectively ensnare most UK and many US companies who have an EU presence or customers, and carbon emissions reporting will become mandatory (from 2023 onwards for the largest companies, and moving downstream to all companies over the next few years).

In 2015, the Science Based Targets Initiative (SBTi) was established to help organisations to set emissions targets in line with climate science and Paris agreement goals. Most UK companies have set targets and are now pushing their suppliers to do the same. This means that most UK and many EU and US companies will have publicly committed to Scope 1, 2 & 3 targets. These aren’t binding commitments, but they have been communicated to the market, and you can view their commitments online (most are incorporated into sustainability reports, and there are also trackers that are keeping an eye on commitments - ZeroTracker is one).

Given than a large and increasing number of (UK/EU & US multinational) corporates have publicly committed to reduce their Scope 1 & 2 Net Zero emissions by a time period between 2025 - 2030, I would expect there to be increasing demand for offsets (or to whatever format offsets evolve into) as their committed NZ 1 & 2 date gets closer. Again, check Zerotracker and the SBTi tracker to see who has made commitments

Most companies are still at the early stages of establishing their decarbonisation strategies, and most have not moved beyond switching to renewable energy and other relatively easy decarbonisation strategies - so while some companies will achieve their Net Zero 1 & 2 commitments (which are generally before 2030), many others will not (scope 3 will be much harder to achieve and may take some industries decades to decarbonise,).

Missing those scope 1 & 2 targets could have a multitude of impacts on companies, from getting pummelled in quarterly earnings calls and AGM’s by shareholders and stakeholders, to consumer boycotts. Their ESG ratings will no doubt suffer, which could in turn impact their access to capital and green/ sustainable finance. Offsets might be the only thing they can turn to in the short term to ask for some absolution.

In response to this dynamic, and with the continuing skepticism about the VCM ecosystem, the offsets market may well evolve into a construct where companies invest in a portfolio of projects across the carbon removal and biodiversity and social ecosystem - which may be easier to communicate to stakeholders and leave companies some wiggle room to innovate with different approaches., particularly as the science and verification techniques improve.

They are likely to use marketplace platforms to buy offsets, and tech-enabled MRV (Measurement, Reporting & Validation) providers to provide the verification (See below for more context on both the MRVs and marketplace platforms).

Companies will be looking for premium projects where they can provide a compelling narrative to their customers and stakeholders. Companies’ marketing departments will likely ramp up here, creating compelling video content of the projects with a strong social & human aspect that they promote on social media.

Companies may also want to tokenize these projects via Web3 technology (blockchain etc) - although this may just serve to confuse everyone, as is the case currently with some startups that have built tokenized, blockchain-powered carbon marketplace platforms that look very much like crypto apps - which (in my experience) are mainly for speculation. However, done properly, it could be a good way for companies to develop their relationships with climate-activated customers & suppliers, and develop their brand accordingly.

To avoid greenwashing claims, companies will want to provide evidence to validate their claims. We are likely to see an explosion in the use of satellite & drone imagery, as well as land, air and sea sensor data to support claims.

eMRV (electronic Measurement, Reporting and Validation providers) are starting to provide this capability for companies to validate their claims - and marketplace platforms such as Patch are integrating MRV providers into their platform.

There are others that are developing this type of data to hold companies accountable (such as CarbonTrace , CarbonMapper, BlueSkyHQ and even NASA) and the likes of Planet provide API feeds that marketplace platforms will likely integrate with.

Emerging market entrants

Emerging market participants such as BeZero & Sylvera are looking to provide ratings to the market, mainly to provide the assurance that the market currently lacks.

These new ‘independent quality enablers’ - or ‘global carbon ratings & risk analytics’ in their marketing, are ‘'AI-enabled technology platforms that use satellite, drone and sensor data to validate projects - underpinned by climate scientists’ research.’

This data is bought by trading exchanges or integrated into VCM marketplace platforms such as Patch - who sell to their customers..

BeZero has taken more than $70m in funding since its inception in 2020 - based in London.

Sylvera has taken more than $40m in funding since its inception in 2020 - also based in London.

Carbon offset Marketplaces

The likes of Patch and Pledge have evolved to offer a range of carbon offset projects on their marketplace.

They are often integrated into/ partnered with the carbon accounting software companies, who help companies calculate their carbon footprint.

Carbon accounting

Persefoni, Sweep, Watershed and many new entrants are gaining market share in the EU/UK/US - again, this is also a new market, most were founded after 2020, and are replacing/augmenting the Big4 or other consultants who would typically have performed a yearly carbon accounting exercise. Persefoni integrates with Patch, Watershed offer their own offsetting, and Sweep is developing an approach where customers would develop a portfolio of ‘contributions’ to projects.

Buyer drivers

US companies typically are buying carbon accounting software because of compliance (SEC or because their PE investors are asking for it).

UK/EU companies are less compliance-driven and are buying carbon accounting software because they want to use the data to drive decarbonisation efforts - although of course the emissions data will also be needed for regulatory reporting (CSRD etc - see below for regulatory reporting).

Companies can calculate their carbon footprint and then offset some or all of their emissions via the carbon marketplace.

The carbon accounting market is emergent but growing quickly. Its growth will help promote carbon offsetting marketplaces, but the likes of Patch and Pledge are also growing quickly and selling direct to corporates.

Legacy vs evolving Voluntary Carbon Market

The following is an except from an article from CTVC which provides a really good overview of the ‘legacy’ and evolving carbon market:

https://www.ctvc.co/giving-carbon-credit-where-its-due/

With corporates racing to get to net zero, the easiest path forward so far has been through the VCM. Carbon offsets have historically centred on avoided emissions rather than removed emissions and cost as low as $3-5/ tCO2. Despite the question marks around carbon offsets, a ton of avoidance and a ton of removal have thus far been treated equal in the corporate net zero ledger. Pricing per ton incentivises companies to buy the lower-quality avoidance offsets.

To frame this in real world terms, Amazon’s carbon footprint in 2020 was 60M metric tons of CO2. Assuming no decarbonisation activity, if they spent $3/ tCO2, they would have only needed to spend $180M to offset their Scope 1-3 emissions – a 0.05% drop in the bucket compared to their $386B in revenue. The carbon offsets market as it stands today provides an ‘out’ for corporates to falsely claim Net Zero while paying pennies on the dollar.

“The reason most people buy offsets is to compensate for tons of CO2 emitted in their internal processes. Because those fossil emissions will have a permanent impact on climate, and companies sometimes buy impermanent offsets purely based on price, that trade is quite bad for the environment and the net carbon arithmetic doesn’t tie,” notes Jonathan Goldberg, CEO of Carbon Direct.

As buyers grapple with the multifold problems of the VCM (above), corporates have started to demand quality. With some leading buyers willing to pay a premium, the carbon market is gradually bifurcating between legacy emissions reductions and the evolving supply of carbon removals. But removals don’t come cheap today, with engineered carbon removal at $500+ per ton, and nature-based removal running at $20+ per ton.

The legacy Voluntary Carbon Market

In the legacy market, a corporate with net zero commitments can set their carbon budget for offsetting, work with middlemen to find offsets at the cheapest price, and wipe their hands clean to continue operating as usual and pumping out emissions.

Pledge net zero and conduct emissions accounting. The first step after any feel-good corporate net zero announcement is to actually understand their emissions footprint. It’s extremely heterogeneous and challenging work, especially when relying on off the shelf emissions factors which can vary a carbon footprint by many multitudes.

Purchase carbon offsets. Once corporates have completed the hard work of measurement and mitigation, the carbon offsets market can plug the remaining gap. Brokers advise and help corporates construct carbon offset portfolios - think of them as carbon asset managers who help corporates purchase OTC carbon credits. Corporates give their target amount and price point, so brokers can hunt down credits from project developers. Given these budgetary dynamics, brokers must prioritise offsetting emissions at the right cost over legitimate quality.

Examples: 3 Degrees, South Pole, Bluesource, Karbone, Evolution Markets, Natural Capital Partners

Supply carbon offsets. On the other side of the market, the Registries act as the gatekeepers for certified credits. They’re typically nonprofit orgs that oversee the registration and verification of carbon offset projects. Certified projects have to go through the hoops of meeting the registry’s methodology including a manual validation/ verification process (think people on the ground wrapping measuring tapes around trees). Only then are the credits eligible to be listed and traded on the registry’s marketplace.

Examples: American Carbon Registry, Verra, Gold Standard, CAR

Where there are credits and projects, there are developers. Project developers work with landowners to assess projects, bring in investors, and develop/sell the credits generated. The two broad types of carbon offsets are renewable energy projects and land use projects (e.g., improved forest management).

Developers get to take a hefty 20-40% cut since they have the inside scoop in what’s otherwise a very opaque market. Similar to the renewables world, developers will build a 20 tab excel model to project cash flows - but instead of electrons they estimate carbon. Since the maths is hard to check, there’s wiggle room and loopholes for developers to exaggerate assumptions for optimal carbon credit generation (for example, a higher growth rate factor makes the avoided emissions pie much bigger).

The Evolving Carbon Market

Given the flaws in the legacy market, corporates are seeking quality from their stakeholders and numerous innovators have heeded the call to create new carbon management, removal, marketplace, and verification tools.

A few forces at work are driving the evolution of this new carbon market:`

Accessibility: new tech-enabled entrants with the ability to span farther down the value chain (e.g., platforms acting as both ratings agencies and verifiers - notable BeZero and Sylvera)

Technology: technology developers developing removals rather than project owners, ‘upping’ the tech level across the chain (e.g., permanent direct air capture and sequestration)

Transparency: better tools and methodologies enabling clarity and quality in the market (e.g., Stripe and Microsoft open sourcing removal RFPs and publishing through the NFP Carbonplan )

Pledge net zero and conduct emissions accounting. A new ecosystem of carbon accounting software has sprung up overnight (such as Persefoni, Sweep and Watershed) to automate what was once the job of consultants with spreadsheets. After the data is served, platforms like Watershed have started to slip downstream by developing an in-house carbon removal marketplace directly integrating removals purchasing into the carbon accounting flow.

Other leading carbon accounting platforms such as Persefoni have integrated with offset platforms such as Patch.

Purchase carbon removals - Direct Procurement

In typical SaaS D2C (Direct to Consumer) nature, new tech entrants are enabling corporates to directly procure carbon credits sans brokers and middlemen.

Unlike the legacy market of carbon offsets with vintages or emissions reductions generated in the same year that the credits were issued, carbon removals are often sold as “future vintages”.

Many of Stripe and Microsoft’s purchases are commitments to supporting projects removing carbon in the future.

Think of it like a removals version of a renewables PPA - or CPA (Carbon Purchasing Agreement) - where the offtaker signs a long-term contract to purchase carbon removal directly from the generator.

Stripe sparked the carbon removal conversation when they kicked off their RFP for carbon removal credits and set their willingness to pay at >$1000/ tCO2 to accelerate these technologies down the cost curve.

Instead of working backwards from a carbon budget to match the lowest cost offset portfolio, Stripe committed $1M (independent of tonnage volume) to prioritise actual removal of emissions. Their first purchases included Climeworks, Project Vesta, Charm Industrial and Carbon Cure ranging from $75-$750 per ton of carbon removed.

Since then, over 10,000 of Stripe’s own customers now contribute to purchase carbon removal through Stripe Climate. Stripe and its customers have now contributed a total of $15m across 14 carbon removal projects: with a batch of purchases in Spring 2021 followed by one in Fall 2021.

Microsoft holds the most ambitious climate pledge, committing to be “carbon negative” by 2030. To do that, Microsoft contracted Carbon Direct for advice on high quality carbon removal projects, open sourced their criteria so other interested parties could follow on and replicate, and purchased the removal of 1.3m metric tons of carbon from 26 projects. Many more, like Shopify and Swiss Re, are catching on and prioritising quality over quantity to seek out the best carbon credits.

On the supply side, technology providers like Climeworks and Charm Industrial are also starting to offer direct purchasing options, but given the low volume and high price tag, only individuals and corporates with deep pockets can afford it. To remove the equivalent of 1 person’s emissions, plan to shell out $1175/ month for Charm or $2176/ month for Climeworks.

Frontier is an advance market commitment to buy an initial US$1Bn+ of permanent carbon removal between 2022 and 2030. It was founded by Stripe, Alphabet, Shopify, Meta, McKinsey and tens of thousands of businesses using Stripe Climate.

Purchase carbon removals - Marketplace and Integrated Verifiers

Since registries like Verra don’t certify carbon removal projects, new overlapping entrants in this wild west have emerged to take their place., CarbonPlan and Carbon Direct operate as third party orgs with no direct skin in the game ensuring better quality carbon projects through data and scientists.

Meanwhile companies like Patch and Pledge are creating marketplaces and bundling services to supply high quality removal credits to a wide pool of buyers.

Others are vertically integrating further to combine marketplaces with verification and ratings, including Puro Earth and offset rating agencies like Sylvera and Be Zero.

Pure-play MRV (Measurement, Reporting, Verification) startups are also leveraging new remote sensing technologies to drive cheaper, more accurate measurement, reporting, and verification at scale.

New players in Web3 have driven a renaissance in the voluntary carbon market, including Toucan, Flow Carbon, and Single.Earth. These companies are developing software that enables the tokenization of the credits on a blockchain that can be pooled and traded - opening up to both professional traders and via FinTech apps.

Ultimately, these tech-enabled entrants point to the remaining open question of who fills Verra’s verification shoes for the carbon removal market. We’re still in the early innings of understanding for mechanical and nature-based removal processes like DAC, biochar, soil carbon, ocean CDR, etc. so the jury is still out on whether a standardised methodology can even be applied.

VCM Key takeaways

Legacy verifiers are incentivized for quantity, not quality. Incentives matter. Today, verifiers get paid only when they bring new credit volume into the market. They’re disincentivised to keep low quality stock out of trading.

A quality-aligned alternative would see verifiers compensated for action (evaluating submissions) rather than outcomes (approving new credits).

Counterfactuals don’t exist, so avoided emissions are fatally flawed. Fundamentally, in order to believe in traditional offsets, one must buy into the validity and verifiability of a counterfactual.

Let’s take an example: you own some trees containing 1 ton of carbon. I want to buy 1 ton of offsets so I can pollute 1 ton of carbon elsewhere. You sell me 1 ton of emission reduction traditional offsets, backed on the promise that not only you’ll protect the trees but that if I didn’t pay you, you would cut down the trees.

The counterfactual backs the offset, but of course counterfactuals are hard to prove. What happens if you’re The Nature Conservancy with a stated mission of protecting forests? Could you prove that you’d clearcut without my cash? What if I bought the rights to a new geological formation filled with methane and threatened to drill a hole down to the gas and release it? Who pays me to not drill the hole?

The voluntary carbon market only exists because of corporate Net Zero pledges. Unlike compliance carbon markets, which are driven by government-regulated cap and trade systems, voluntary carbon markets have no other price or quantity driver beyond corporate’s Net Zero pledges.

Compliance systems control the total number of credits in circulation; voluntary systems have no control over the total number of credits.

The definition of Net Zero is still being written. In the absence of regulatory language to define the dos and don’ts of Net Zero, every company has taken pen to paper and written their own strategy – leading to variability in definition and approach.

1 ton of carbon emitted yesterday isn’t the same as 1 ton of carbon captured today. Climate damage occurs immediately. However, the time-cost of additional atmospheric carbon is not accounted for. We need to prorate emissions.

Value likely accrues to those who vertically integrate. Anticipate startups with business models doing everything from originating projects from landowners to selling packages of offsets directly to corporates. If they can defend a specific offset thematic niche (e.g. forestry, soil carbon, etc.) through performing high-quality verification or accounting, startups can circumvent intermediates from taking a cut of revenue.

Corporates buy offsets based on two criteria: price or story. After assessing their current carbon footprint, corporates either approach their offset purchasing with a financial imperative (to spend as little per credit but purchase the full volume of carbon offsets) or marketing imperative (to buy the credits with the strongest aligned secondary messaging e.g. biodiversity, jobs, significant region).

Stripe is a rare outlier that separated total spend from volume of offset purchases, in order to purchase credits (often as the first customer) from CDR technology companies with scaling potential.

Carbon removals make for cheap recruitment marketing and retention. Employees want to align their work and values. By going carbon neutral, and telling a compelling story along the way, corporates can attract and retain climate-concerned employees. In a market constrained more by human capital than dolla dolla bills, 0.06% of revenue is a strong ROI (maths: Microsoft’s $1b carbon removal fund, annualised, is $100m per year compared to $168b FY’21 revenue).

The underappreciated role of carbon insets in decarbonizing Scope 3 supply chains

Here’s another great article from the team at CTVC, which again I’ve copied an excerpt from:

https://www.ctvc.co/the-importance-of-insets-where-mitigation-and-offsetting-mix/

It’s always scope 1 somewhere. Even in the gnarliest supply chains, your scope 3 emissions are someone else's scope 1. For the past few months, we’ve been writing and debating with you about two unresolved, mind-bending climate tech hot topics: carbon markets and supply chain decarbonization. At the bullseye of this Scope 3 carbon offset accounting mess are carbon insets.

Whereas most carbon management frameworks today force us towards acknowledging destructive practices and reducing or covering up their malady, insets give us a view towards a constructive reorganisation of processes and technologies that manage inputs more than outputs.

Carbon insets are still undergoing their transformation, but we think they have the potential to be the Cinderella of decarbonization - ready to be lifted from obscurity to a point of significance, here goes:

Insets not Offsets

The classic net zero strategy guides that decarbonizing Corporates should 1) mitigate, then 2) offset the rest. A hybrid solution to this, carbon insets look like offsets but sting like mitigation. Insetting refers to the intentional reduction of Scope 3 emissions, the upstream and downstream emissions within a company’s own supply chain. Unlike carbon offsets, inset emissions are directly avoided, reduced, or sequestered within the company's own value chain - not sold as a credit to offset another company’s emissions.

The rub is with Scope 3. (For those who could use it: a quick refresher on Scope 1, 2, 3.) Because Scope 3 represents indirect upstream and downstream emissions, those emissions count across multiple parties’ supply chains.

For example, when Cargill produces sugar which gets mixed into a can of Coca-Cola that’s then delivered onto the shelves at Target, all three players count the carbon intensity of the initial sugar production. So, if Cargill’s carbon insetting program accelerates farmers’ regenerative practices, then Cargill, Coca Cola, and Target can all factor in the same emissions reductions to their net carbon balance without “triple counting”.

Demarcating insets vs offsets

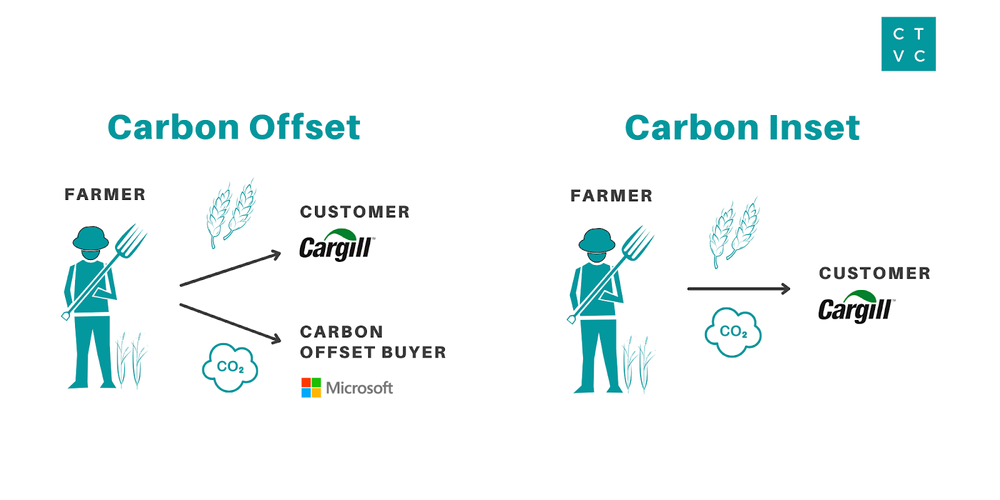

(1) Carbon emissions tracking - who owns the emission reduction?

Carbon offsets: emissions reduction (tonnes) generated travels separately from the physical product

Farmers deliver regeneratively grown wheat to one party (Cargill) then deliver the quantified emissions reduction to another party (Microsoft)

Carbon insets: emissions reduction (tonnes) generated travels with the physical product

Farmers deliver regeneratively grown wheat and the quantified emissions reduction to the same party (Cargill)

(2) Standards setting - who makes the methodology and standard?

Compliance credit: A third party regulatory body like the EU ETS sets the compliance standard

Carbon offsets/ removals: A neutral third party like a registry (Verra, CAR, Gold Standard) or ratings agency (Sylvera) set the certification standard

Carbon insets: The multiple parties involved agree on the standard or methodology used

The Math and Measurement

You can’t inset (or offset) what you can’t measure. Corporate emissions accounting all starts in the same place: the carbon balance sheet. The rub with Scope 3 emissions quantification is the lack of traceability and transparency as an asset changes hands, gets physically transformed, and divvied up. Take an ear of corn as an example - it’s a commodity that’s nearly impossible to trace throughout its lifecycle from field to plate as it goes through harvesting, storage, processing, transformation, packaging, distribution, and sale.

Carbon insets take a clever work-around. Rather than going through the accounting wringer retrospectively to “erase” a corporate’s emissions with another supplier’s offset, insets prevent carbon from being emitted in the first place. Because offsets are a negation of already-emitted GHGs, they must meet rigorous standards of fungibility, additionality, and durability.

Insetting projects do not face the same accounting requirements, in part because they’re not a fungible "credit" like an offset. Insets represent relative emissions reductions, in essence comparing the lifecycle analysis of business-as-usual vs sustainable production. With no external buyers incentivizing insetting projects with credit purchases, there’s less rigor on additionality. Likewise, there’s no need for permanence or leakage because emissions removed through insets never occurred and therefore are inherently permanent and whole.

Regardless of baseline and insetting standards, industries with difficult-to-track embodied emissions, like agriculture, still require technology innovation in Scope 3 MRV (Measurement Reporting Verification) to quantify verifiable reductions.

Inset Adoption is ripe in Food & Ag

Though insets are relevant across a breadth of industries, to-date the food & ag supply chains have had the greatest appetite for insets for a number of agriculture-specific conditions:

👩🏼🌾 Low-hanging, low-carbon fruit. Ag practices already exist for decarbonizing food supply chains using nature-based, highly scalable solutions. Relative to new technologies for cleaning up hard-to-abate industries, ag decarbonization is much lower cost. The key is pricing incentives.

💸 Existing financial mechanisms. There are financial systems already in place to incentivize farmers to employ regenerative practices. No new payment systems needed here.

🥧 Big pie. Agricultural soils are arguably the world’s largest carbon sink.

🍴 Consumer-facing. Food is quite literally in our faces. Ag cos are therefore often the first to face the music on consumer sustainability sentiment.

🌱 Sustainability co-benefits. Decarbonizing food supply chains also produce other good stuff like biodiversity, water and air quality, and nutrient-dense food.

As insetting is still nascent, even in ag, there are no centrally defined requirements or standards like in the offsets world. As the lens here matures, insetting discovery, measurement, and qualification will evolve from a secondary criteria to offsets to a primary means of thinking through net carbon impact. What this looks like is an overhaul of the approach of ‘reduce and pay for the bad’ to ‘design processes for good’

Carbon Insets in the real world

In the Carbon Insets value chain, the emissions reduction is kept within the supply chain, rather than sold to another outside party. Let’s walk through an example: a farmer signs up with Truterra (a project developer) and decides whether to participate in offsetting or insetting.

⬅️ Offsetting: The farmer delivers regeneratively wheat to a downstream customer, in the process creating offsets which Truterra submits to a registry. Once the emissions reduction is verified, the registry certifies the credit which TruTerra then sells to corporates outside the supply chain. Farmers get additional revenue through the sale of the credit.

➡️ Insetting: The farmer delivers regeneratively wheat to a downstream customer that Truterra has contracted. The customer pays a premium for that sustainable wheat and the farmer gets additional revenue through the price increase.

The key difference for the farmer is the mechanism through which they get compensated, which can vary both price and timing. The distinction between insetting vs offsetting is whether the sustainability claims are attached or detached from the crop.

The Carbon Insets Value Chain

🧑🌾 Inset Suppliers. Farmers employ regenerative practices to grow crops that reduce and/or sequester GHGs and get paid per metric ton of carbon.

👷🏽 Project Developers. Organisations that work with farmers to implement insetting programs and partner with downstream corporates to deliver emissions reductions (insets) within their supply chains. [Truterra, Indigo Ag, EcoHarvest, Practical Farmers of Iowa, The Nature Conservancy, SustainCERT]

Innovator: Truterra is a 1,900 farmer-strong sustainable project development business of the member-owned cooperative Land O’Lakes. Says Truterra president Jason Weller, “Truterra works with farmers and their trusted advisors to change the way they farm and be rewarded for those changes. That can look a little different for each farm. Some might plant a cover crop between their commercial crops to keep the soil covered and roots in the ground year round to increase how much carbon the soil sequesters, creating a potential carbon offset. Other farmers might park the plough and just plant directly into soil that has not been tilled. Now you’re looking at fewer emissions from the tractor, which could contribute to a potential insetting program. Truterra focuses on helping farmers and their advisors make these changes successfully and also connecting farmers to the companies and organisations who want to support these changes and the positive climate impacts they create. In our first carbon program in 2021, those changes removed nearly 200,000 metric tons of carbon and returned nearly $4 million to those farmers who did the work. That’s a total win-win.”

👨🏼💼 Supplier. Ag retailers and distributors between the farmers and downstream customers. [Bayer, Corteva, Nutrien, Yara, Cargill]

👨👩👧 Customer. Downstream customers that purchase raw commodities like wheat as key inputs in their products. [AB InBev, Nestlé, Campbell, Danone, Unilever]

👮🏾 Standards. Certification bodies that develop best practices for insets.

Innovator: SBTi FLAG project is developing methods and guidance to enable companies within nature-based sectors to set science-based supply chain targets including land-related emissions and removals.

👩🏻💻 MRV. Supplies data to verify carbon outcomes from the pursuit of insetting methodology.

Innovator: Last week, Perennial raised an $18m Series A from a coalition including Temasek, Bloomberg, and Microsoft to measure soil carbon and farmland emissions using satellite-based machine learning models. With this methodology, Perennial produced the first ever 10 metre soil carbon map of the continental United States, unlocking the ability to quantify field-level carbon metrics with few to no physical soil samples. Perennial’s technology allows low- to no-touch emissions monitoring, enabling much easier systems for calculating and applying insets, even deep down the supply chain.

Perennial’s soil carbon map, capable of showing soil carbon levels to an acuity of 10m. Methodology includes layering location-specific data from a proprietary soil sample archive with a ML satellite remote sensing model.

Carbon insets Key Takeaways

Where to draw the line? The definition of mitigating vs insetting remains blurry. One company’s Scope 1 is another’s Scope 3. So far the line has been drawn as Scope 1 + 2 are to mitigation vs Scope 3 is to insets. This raises headscratchers like: how to categorise switching to a clean electricity source? A building owner who uses that electricity to keep the lights on likely claims mitigation. However, if that clean electricity is used to produce decarbonized cement which is then used in the walls of the same building, the building owner could count the reduced carbon intensity as an inset.

Levelling with double-counting. While it’s valid for multiple owners to account for the inset as the physical good moves down the supply chain, double-counting can run rampant when offsets and insets are created from the same emissions reduction action (e.g., if an offset buyer (Microsoft) and inset customer (Cargill) both claim the same sustainability benefit on their books). Takeaways hold from our longer supply chain feature on traceability and transparency.

Ag today, but everywhere tomorrow. While insetting has primarily been isolated to food & ag supply chains to-date, expect wider adoption - particularly in vertically integrated industries with heavy Scope 3 emissions and clear shared decarbonization incentives (e.g., low-carbon metals for batteries, beneficial to EV OEMs and energy storage cos).

Where’s the referee? Since offsets are internal to a corporate’s supply chain, registries and third party certifiers have been sidelined. Likewise, inset MRV standards and accreditation are, right now, divorced from that of offset MRV compliance - and much more lax. Without the requirement for additionality and temporality considerations, it’s essentially up to the producers and consumers themselves to agree to a methodology, which MRV players then duly provide the component data for.

WTP for practices, not MRV. Going even further, some programs ditch the MRV quantification entirely and are willing to pay for qualitative practices (e.g. cover cropping, no till). While simple to verify, the climate impacts are unknown or estimated.

Shift to fungibility. The next evolution of Scope 3 inset accounting will likely decouple physical assets from their carbon impact, allowing for the tokenization of impact - and more closely resembling offsets.

Prime example: Eco-Harvest, an inset credit program which rewards producers for beneficial environmental outcomes from regenerative ag while decoupling the physical commodity from its (negative) emissions.

This approach has the potential to rewrite the way farmers are rewarded for their regenerative practices, while simplifying mechanisms for food, fibre, and fuel companies to lower their Scope 3 emissions.

Net Zero is not a zero sum game. Technically, adoption of insetting will decrease demand for offsets. Though realistically, complete supply chain decarbonization is unfeasible today. Expect increased price appreciation of (nature-based) removals intra-supply chains as internal carbon pricing analytics improve and awareness builds around breakeven carbon pricing.

Summary

The key observation is that the VCM is evolving, with emergent tech players slipstreaming the likes of Verra and Gold Standard to provide a more scaleable, transparent and dynamic market for both corporate customers and investors.

Incoming regulation, in addition to market & investor pressure, is forcing companies to set Net Zero targets and begin their decarbonisation efforts. This is true across all geographies, although the US for now is more driven by compliance (carbon emission disclosure to the SEC and their Private Equity investors) than actual decarbonisation efforts - and thus access to a well functioning VCM is an even more attractive proposition to US companies and investors.

The VCM is likely to explode over the next decade in response (Societe Generale and others estimate anywhere between a $80bn - $150bn market by 2030).

If we also look at the emerging Voluntary Biodiversity Market then the TAM across carbon and biodiversity markets could even double or triple in size. We are awaiting final proposals from Mark Carney’s Taskforce for Nature-related Financial Disclosure TNFD, which is currently in the final beta stage. This will have a catalytic force on investors to start taking into account nature and biodiversity in the companies they invest in. In its own words, “Nature loss poses a major risk to businesses, while moving to nature-positive investments offers opportunity. The market-led, science-based TNFD framework will enable companies and financial institutions to integrate nature into decision making.”

Sources:

https://www.msci.com/www/blog-posts/introducing-the-carbon-market/03227158119

https://climatetechvc.substack.com/p/-the-missing-link-to-net-zero?s=r&ref=ctvc.co

https://www.ctvc.co/giving-carbon-credit-where-its-due/

https://www.ctvc.co/the-importance-of-insets-where-mitigation-and-offsetting-mix/

https://www.iosco.org/library/pubdocs/pdf/IOSCOPD718.pdf

Carbon offset Taxonomy

The different types of carbon offsets:

Source: https://www.smithschool.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/2022-01/Oxford-Offsetting-Principles-2020.pdf